Contents

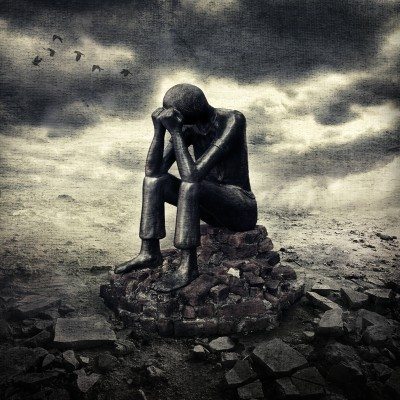

The limits of our thinking, and the shape of our instinct.

This essay starts off by discussing the limits of human reasoning, moves into an examination of our basic sub-rational drives (and how we ourselves exploit those drives to survive, with hideous consequences), and ends with an eye towards how we might redeem ourselves.

How Large the World?

The more I think about what we humans are up to, the more obvious it is that we don’t know what we’re doing. A good way to describe humanity: a race of beings on a small planet, trying to figure out what we should be up to.

For most of human history (this phrase appears often in my pages), we did not even know we lived on a single small blue planet. Each nation believed itself to be the sole (or at least most important) race of people; voyagers were rare, visitors rarer. Life was governed by the cycle of the seasons.

Most economies were agriculturally based, and most societies were rigorously constructed to limit population to that which could be supported by the year’s harvest. Most governmental decisions affected only the local community; humans did not yet have the ability to drastically change the face of the planet. Individual wealth was limited by society’s ability to produce, which was in turn constrained by the narrow agricultural and technological knowledge at our disposal.

Technology gradually began to change this picture. Over time, we became more able to consume large tracts of land, or vast quantities of natural resources, in order to spread material wealth through our societies. And as is natural for hungry, cold apes, we wanted to give ourselves an abundance of food and comfortable living places. This was just a simple extension of how we’d always lived, only augmented by our new knowledge of how to change the world to suit ourselves….

The more important effect of these technologies, however, is they magnified how large an impact we humans would have on the world. A present-day American consumes three hundred times as much as a native of Ghana. We have removed the link between how much we need to survive and how much we take for ourselves. And with this disconnection comes a crucial challenge to our powers of reason.

When we can consume more than we ever believed possible, just by dint of living in modern society, we must realize that our actions have impacts that will only be felt years or decades from now. And this is a new challenge to human reason. We are not innately well suited to think about dangers that are years in the future. Up until the last few centuries, we humans were not able to imagine, let alone create, such dangers. Now we have surrounded ourselves with them.

This is perhaps the biggest challenge we face: by creating the lives we want to live, we are doing damage the likes of which we have never had to think about. To understand this dilemma more deeply, we need to look at who we are.

Our Basic Selves

Human reason only emerged a relatively short while ago, as reckoned in evolutionary time. Most of our drives and instincts have little to do with thought. This causes all sorts of problems when we believe ourselves less animalistic than we are.

At bottom, humans are social animals. We need other humans to survive. It is not easy to maintain sanity in isolation. Being ignored can feel life-threatening, and often actually is. Attention hunger is one of our main survival instincts.

Even the physical aspect of survival is a trouble spot. For most of human history, it was all we could do to get barely enough to live on; today many have more abundance than they could ever need to survive, yet they hunger for more.

Our fight-or-flight response is another one of our deepest traits. When your survival is threatened, aggression is the natural response. Unfortunately, survival threats in the civilized world come in many new non-physical forms, yet our bodies still respond physically.

These three drives together–attention, hunger, and anger–shape the world we’ve wound up with, and constrain our thoughts of the future.

Silence = Death

A dramatic film I once saw opened with a baby sitting in a chair, facing its mother, happily playing with her. Then the mother turned away from the baby, ignoring it. The baby went from smiling to quizzically frowning to full-on bawling. When very young, attention from our parents is literally life or death.

Even as we become older, it is easy to find solace in others. We create our sense of the world in partnership with the people we spend our lives with. This can have disastrous consequences, if we become involved with groups seeking control over us. It is often easier to go with the flow than to find your own path, until late in life, when you realize you have not paid enough attention to yourself.

The Web is a new forum for finding an audience. Yet even here, many home page writers sound literally desperate for viewers. Without viewers, they seem to think, my site will be nothing. Again, other people are important, but you yourself may be more important. (See my home page bit. Warning: side-link.)

Daytime talk shows provide another example of the hunger for fame. People eagerly expose the most tawdry and personal aspects of their lives in order to make an impression on the world. Emotional trauma is nothing if it means another million viewers. Mass media distort human behavior, by creating audiences larger than ever before possible, and focusing the audience’s attention on only the most shocking of incidents.

Insecurity, the basis of advertising

Not only socially, but personally, we need attention. American culture tells us, incessantly, that without a life partner we are not complete. If you do not have love in your life, you are not a whole person, the message goes. While love is important, lack of love is not necessarily fatal. Yet more people try to transform themselves into ideal lovers than try to find themselves and let love come to them. ***

Almost the entire American advertising industry is based on attention hunger. The ads exert incredible effort to attract our attention, in order to convince us that we will not be sufficiently attention-getting unless we emulate the people in the ads. We are told again and again that we are not complete, that in order to get the love and acknowledgement we are told we need, we must spend, spend, spend.

Money cannot buy love or happiness. Therefore love or happiness are not for sale; only surrogates are available. We are drowned in a sea of images of what love supposedly looks like, yet the more we try to emulate those images, the more out of touch we get with who we really are. The appearance gets confused with the reality.

Los Angeles is a fascinating city, being the epicenter of this dynamic. Los Angeles is a city of image: who you can get to notice you determines who you can become. LA is a vortex, attracting audience attention and money, converting it into impossibly-beautiful images, and sending it back out. We are hypnotized by the super-attractive sights and sounds, and spend impossible amounts of effort trying to become the ever-more-freakish models that surround us.

Survival instincts

Silence may = death, but so does starvation, and so does murder. We need food, shelter, and safety to survive.

We are better able today than ever before to procure food and shelter for everyone. Yet the gap between rich and poor is wider, worldwide, than it has ever been. Why is this? Where do these injustices come from?

Not only do some feast while others starve, but many–perhaps most–people feel unsafe living in today’s world. We are beset by threats–environmental, political, racial, financial. It is a hugely complex world, with many menaces. Our range of responses is all too limited.

How much is enough?

Insecurity drives advertising in the material realm as in the romantic realm. No matter how much you have, you can always have more. And moreover, the less you have, the less you are. Many of the images we are showered with carry the implicit subtext, “You, too, can have all of this!” Never mind that the cost may be horrendous damage to the world, and total personal confusion… the more you have, the more you may find yourself wanting, in which case wealth will lead to sorrow.

Is all this malicious? Why are we told we need more than we do? It is not only the audience that is insecure–the advertisers themselves are desperate. Without viewers, advertising is a waste of money. Without shoppers, firms go out of business. Advertisers do whatever will make viewers feel least secure, because advertisers are themselves terrified.

Capitalism in general is fraught with problems, as it tends to produce exploitative systems that feed on people’s insecurities, in order to swell and become even more successful at draining people. It is a lot harder to help someone find themselves than it is to sell them what you’ve got and call it a solution to their problems.

Who is a threat?

Throughout history, humans have evolved ways to distinguish ourselves. Tribe, race, nation; deity, religion, morals; guild, profession, job; sex, sexual orientation, sexual preference. Yet underlying it all is the fundamental distinction of “us” and “them”. Any dividing line separates the world in two, and any such line can generate tension, when the people on one side start to see the others as a threat.

Our survival instinct can be invested in the groups we feel ourselves part of. And when the group is threatened, we ourselves feel attacked. White supremacists consider every non-white baby to be an encroachment on their domain. Environmentalists see poison in every cloud of smoke. Corporate employees go on the warpath against their competition.

All these confrontations reach down to the same old hormonal system that we once used to escape from predatory animals. Regardless of whether our life is actually in danger or not, we get tense, we get angry, and we ultimately are exhausted. Yet that fight-or-flight response can give us focus, even purpose. So all our discussions become battles, and all our battles wars, as we take everything personally.

The addictions of violence

Fight-or-flight is relied on not only because it provides drama and structure, but because anger is gratifying. It feels good to get mad, sometimes.

We evolved in a world in which anger and aggression was an essential part of life. Yet now they can be liabilities as often as assets. Does this mean that anger is wrong? Should we strive for an aggression-free world?

I’m not sure that’s a sensible question, wired as we are for anger. I don’t think disavowing our human qualities is a wise way to live. But there are many troubling issues with expressing your mad.

Sports, athletic and real

Professional sports are distilled aggression. The quest to win becomes the focus of staggering amounts of money and attention. Many of the most popular sports are also the most violent, and then there are mock sports like American Gladiators, which go even further towards comic-book violence.

Not only are we confronted with war on the playing fields, but true-crime TV shows tell us about the war in our own neighborhoods. It’s the cops versus the bad guys, with no halftime, and you could be the star! The more we swim in images of violence, the more we come to think violence is the best way to deal with problems. Young children, weaned on gang-banging culture, become sociopathic killers before becoming teenagers.

This can be taken too far; ancient myths are quite bloodthirsty themselves, and children have always played bloodcurdling games with one another. But as we increasingly find ourselves able to live any way we choose, violence can seem downright appealing, and–again–whatever is appealing will be exploited. (Witness extra-bloody video games and movies.)

War is heaven

For people facing a bleak and dull life, war can be a step up. Most gang crimes are not performed by drug dealers; the most criminal gang members are in it for the thrill. Throughout the world, peoples facing hardship and deprivation often go to war to get their minds off their problems. And though war may not improve lives, it certainly makes them more exciting.

Reasons for hope

Humans may be awfully predisposed to live according to these drives, but there are other possibilities. Here are some:

Most societies consider a high birthrate essential for survival, but more and more, we are finding that given a choice (and the tools needed to choose) women and men will have smaller families. We can channel our survival desires in good directions as well as bad.

Violence may be ubiquitous, but there are safe ways to express it. Humans can distinguish fantasy from reality, and frequently do. Perhaps the fascination with true crime will wane… some gangs are already signing truces, and some schools becoming weapon-free.

Mass media have distorted our culture enormously (see the cover article of the latest Wired for more on this). But people are getting fed up with being spoon-fed the truth, and an opening exists for a new flowering of individual views.

Technology has caused a lot of damage to the planet, but new technologies *** may not share the same damaging qualities.

New discoveries about human happiness point the way, albeit tenuously, towards life goals that might work better for everyone. People are recognizing that exploiting our basic impulses may not get us very far towards truly fulfilled lives.

The better we understand ourselves, the better we can choose how we want and plan to live, and the better we can integrate all of ourselves in the pursuit of what is truly important.